You might as well start playing this now. Enjoy.

While we

have been reading through the Gospel of Mark over the past few classes, you may

have asked yourself why this book was chosen as part of the Canonical Gospels,

which also includes Matthew, Luke, and John (Waterworth, 1848). There are many

other gospels, or stories about the life of Jesus, that were written and

considered for inclusion, but denied canon during the Council of Trent. These

include the Gospels of Philip, Judas, Truth, and Perfection, to name a few (Koester,

1980). What makes the common four so important to be included in one of the

most widely read sacred texts?

The Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are so called because they “see together,” or have the same point of view. They definitely live up to that name; many of the events recorded in one are shared by the others, such as John the Baptist, Jesus’s baptism, Jesus’s temptation, various healings and parables, Peter’s confession (and denial), Jesus’s transfiguration, and the plot to kill Jesus (“The Order,” n.d.). Many scholars affirm there existed what is referred to as the mysterious “Q source.” This document and the Gospel of Mark are considered to be the material from which the other Synoptic Gospels drew (Lührmann, 1989).

The Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are so called because they “see together,” or have the same point of view. They definitely live up to that name; many of the events recorded in one are shared by the others, such as John the Baptist, Jesus’s baptism, Jesus’s temptation, various healings and parables, Peter’s confession (and denial), Jesus’s transfiguration, and the plot to kill Jesus (“The Order,” n.d.). Many scholars affirm there existed what is referred to as the mysterious “Q source.” This document and the Gospel of Mark are considered to be the material from which the other Synoptic Gospels drew (Lührmann, 1989).

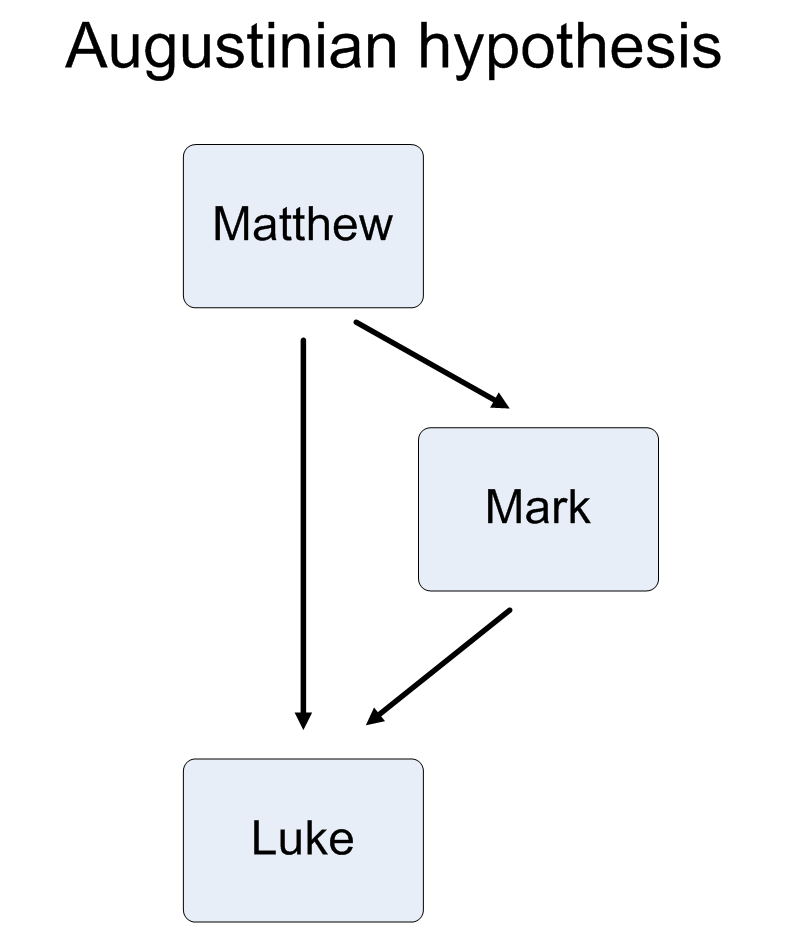

The

Augustinian hypothesis claims, however, that the Gospel of Matthew was the

original source of material for the later Gospels of Mark and Luke. This

hypothesis also claims that Luke borrowed material from Mark (Thomas, 2002).

The Q source is completely ousted with this theory.

Another

theory that exists concerning the Synoptic Gospels is the Farrer hypothesis.

This claims that Mark was written first followed by Matthew. Luke then borrowed

from both of these (Farrer, 1955). With the shared styles and recorded events,

this claim boasts much regard.

Whichever

theory may be correct – or, none of them may be correct – the Gospel of John

still must be discussed. Why is this one different from the other three? The

authorship of John has been long disputed. Its writing style and wordage bears

much resemblance to the three epistles credited to John’s penmanship. Indeed,

the first chapters of both the Gospel and 1st John share very

similar wording about the manifestation of God as Jesus and calling Him the

Word and the Light.

When I have read through the

Gospels before, I felt a different undertone with John. John seemed to tell a

more evangelical and proselytizing story. That is to say, it was a more

awe-inspiring and persuasive one to me. It felt like John – or whoever the

author was – was trying to convert me. Phrases such as “eternal life” are

employed much more frequently. It’s also noteworthy that Jesus’s mother is

never mentioned throughout the whole book.

The Gospel of John largely owes its

inclusion in biblical canon to the work of Irenaeus. Irenaeus lived from 130 to

202 and was the disciple of Polycarp. Polycarp was a disciple of John (Richardson,

1953). So if John really was the author of his Gospel, it would make sense that

Irenaeus would endorse it fervently. Another thing Irenaeus did fervently was

fight Gnosticism, a school of thought that significantly downplayed Jesus’s

divinity (“Irenaeus, Bishop,” n.d.). As I’ve already mentioned, John’s Gospel

drives the idea home that Jesus is God is Jesus is God is Jesus. Of course,

those Gnostics would hate this idea, and Irenaeus could use it to dissuade

others from their heretical teaching. From then until today the Gospel of John

has held a place in the Bible along with Matthew, Mark, and Luke. All four of

them unite together to create an image of a man living in Israel who is

followed by millions of people still today.

|

| Matthew, Mark, Luke, John... and the heart guy... |

[electronic image of Planeteers uniting in power to summon

the awesome Captain Planet]. Retrieved April 21, 2013, from: http://cragmama.com/wp-content/uploads//2012/06/ThePlaneteers.jpg

Farrer, A. (1955). On Dispensing With Q. Studies

in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R. H. Lightfoot. Retrieved from http://www.markgoodacre.org/Q/farrer.htm

Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyons, Theologian. Retrieved from http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bio/194.html

[iSSerDc]. (2007, July 3). pachelbel's Canon in D--Soothing music(the best version) [video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOA-2hl1Vbc

Koester, H. (1980). Apocryphal and Canonical Gospels. The Harvard Theological Review, 73(1/2),

105-130.

Lührmann, D. (1989). The Gospel of Mark

and the Sayings Collection Q. Journal of

Biblical Literature, 108(1), 51-71.

McOnroy (designer).

(2007). The Two-source

Hypothesis to the synoptic problem [electronic image]. Retrieved April 21,

2013, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Synoptic_problem_two_source_colored.png

McOnroy (designer).

(2007). The Augustinian hypothesis solution to the Synoptic problem [electronic

image]. Retrieved April 21, 2013, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Synoptic_problem_-_Augustinian_hypothesis.png

McOnroy (designer).

(2007). Farrer hypothesis solution of the synoptic problem [electronic image].

Retrieved April 21, 2013, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Synoptic_problem_Farrer_hypothesis_.png

Richardson, C. (1953). Early

Christian Fathers. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

The Order of the Triple Tradition in the Synoptic Gospels.

Retrieved from http://www.mycrandall.ca/courses/ntintro/OrderTriple.htm

Thomas, R. (2002). Three views on the origins of the Synoptic

Gospels. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic &

Professional.

Waterworth, J. (1848). Canons

and Decrees of the Council of Trent. London.

No comments:

Post a Comment